VP Law Firm • nov 04, 2020

Misleading advertising and failures of due diligence

Businesses throughout Europe and globally are increasingly confronted with misleading advertising and a growing variety of phishing schemes, a form of cybercrime in which they are lured into disclosing sensitive information. There are many companies for which phishing is virtually a core activity and which use such advertising ploys to earn income in a way that is certainly unethical, if not outright illegal. The targeted businesses consider themselves injured even though they have credulously fallen into the trap by obviously failing to exercise due diligence. These issues are ultimately settled by the courts, which are given the thankless task of applying principles (rather than concrete rules) to decide whether to extend legal protection to the advertiser, who has obviously engaged in misconduct, or the unwitting user of the service, who has obviously not been sufficiently careful.

Misleading advertising is regulated by Article 11 of the Serbian Advertising Law (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia, Nos. 6/2016 and 52/2019 – Other Law), which reads:

[1] Misleading advertising is prohibited.

[2] Misleading advertising means any advertising which in any way, including its presentation, deceives or is likely to deceive the advertisement recipients and which, by reason of its deceptive nature, is likely to affect their economic behaviour or which, for those reasons, injures or is likely to injure a competitor

[3] In determining whether advertising is misleading, account shall be taken of all its features, and in particular of any information it contains concerning:

1) the characteristics of goods or services, such as their nature, composition, availability, quantity, specification, method of use, fitness for purpose, geographical or commercial origin, method and date of manufacture of goods or method and time of provision of service, results to be expected from the use of goods or services, or results or other indicators of tests or checks carried out on the goods or services;

2) the price or the manner in which the price is calculated, and the conditions on which the goods are sold or the services provided

3) business information, attributes and rights of the advertiser, such as his identity and assets, his qualifications, commercial property or intellectual property rights or his awards and distinctions.

Infringement of these provisions is a misdemeanour for which a legal person may be fined between 300,000 and 2 million dinars.

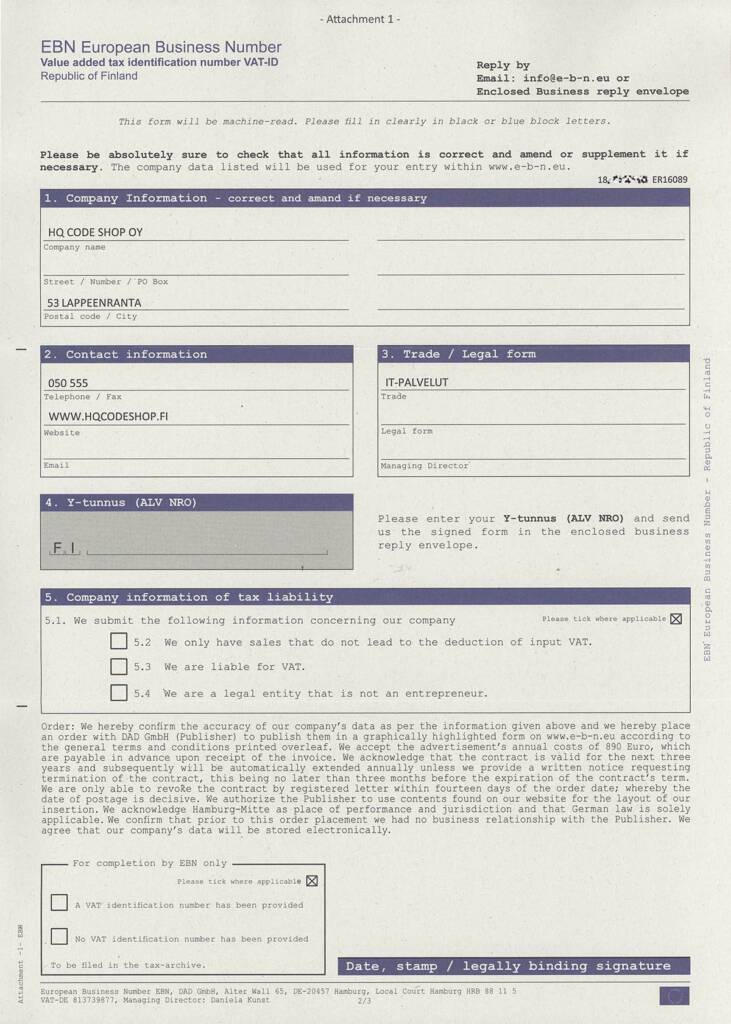

Case study: Advertising by DAD Deutscher Adressdienst

The German company DAD Deutscher Adressdienst GmbH, based in Hamburg, operates the European Business Number web site (e-b-n.eu). The company targets firms throughout Europe by sending official-seeming forms bearing the title ‘European Business Number’ which at first sight appear to solicit only confirmation of business register data, in particular the recipient’s taxpayer identification number (TIN). A closer examination reveals a section of fine print detailing the cost of the ‘service’, which depends on the target country but is usually 771 euros annually, adding that the ‘contract’ will remain effective for the subsequent three years unless terminated within three months before the expiration of its term or revoked within 14 days after the form is sent. The note stipulates Hamburg-Mitte as the place of performance and jurisdiction and requires the exclusive application of German law. The EBN web site publishes information about companies that send in completed forms, allegedly to help them attract customers, which is the explanation commonly given by DAD to justify the fees it charges.

Appearance of the controversial form

The fine print on the form sent to targeted companies includes the word ‘order’, which in this case means that the firm that completes and returns the form actually issues an order to EBN/DAD to publish its data at e-b-n.eu, as well as that doing so actually means the recipient and DAD have entered into a legal agreement and that the recipient has accepted all the terms and conditions of that agreement, including the jurisdiction of the Hamburg court and the applicability of German law. The lower right-hand corner of the paper carries a stylised official symbol of the European Union, lending an additional veneer of credibility to the form.

European experiences and practice

Many European countries are faced with similar misleading types of advertising, but courts have taken differing views about whether claims arising from these contracts are actually enforceable, which has given rise to the development of diverse body of case law.

For instance, a court in the Czech Republic ruled in favour of DAD when it sought to collect payment from a Czech company. By contrast, a German court (judgments Az 822 C 420/09 of 5 March 2010 and Az 309 S 66/10 of 14 January 2011) found this was a case of fraud, that the goal of the form was to mislead the recipient by offering a non-existent service and dishonestly extracting money from the recipient, that the recipient was purposefully misled by DAD, and that there was intent to deceive, whereas the recipient was negligent in not carefully reading the terms and conditions, which was however found immaterial to the ruling. Finally, the court noted that the judgment was not generally applicable and that each individual case would have to be assessed on its merits.

Efforts to tackle this fraud have reached the European Parliament, which in 2014 declared admissible Petition 1176/2013, filed by a French business targeted by DAD. In its Notice to Members, the European Parliament cited Article 2 of Directive 2006/114/EC of the European Parliament and the Council, which defines misleading advertising as: ‘any advertising which in any way, including its presentation, deceives or is likely to deceive the persons to whom it is addressed or whom it reaches and which, by reason of its deceptive nature, is likely to affect their economic behaviour or which, for those reasons, injures or is likely to injure a competitor’. Moreover, in line with Article 5 of the Directive, Member States are required to: ‘ensure that adequate and effective means exist to combat misleading advertising and enforce compliance with the provisions on comparative advertising in the interests of traders and competitors. Such means shall include legal provisions under which persons or organisations regarded under national law as having a legitimate interest in combating misleading advertising or regulating comparative advertising may: (a) take legal action against such advertising; or (b) bring such advertising before an administrative authority competent either to decide on complaints or to initiate appropriate legal proceedings.’

This issue was discussed at numerous businesses forums throughout Europe.

Serbian experiences

One Serbian example also reveals the variety of types of misleading advertising and instances where companies fail to exercise due diligence in allowing themselves to be taken in.

In the latest in a long line of similar scams, Digitalna Platforma d.o.o. Beograd of New Belgrade, a firm incorporated on 14 February 2020 as a market research and opinion polling company, sent official-looking invitations for listing on its web site at privredni-registar.rs.

The firm sought a fee of 4,500 dinars and included pre-filled payment orders, warning that the cost would rise to 15,000 dinars if payment was not made by 12 October 2020.

The firm sought a fee of 4,500 dinars and included pre-filled payment orders, warning that the cost would rise to 15,000 dinars if payment was not made by 12 October 2020.

Serbian regulations

The lack of practice in Serbia has been causing much doubt and insecurity amongst businesses that have been deceived and/or suffered damages as to how to protect themselves against such misleading advertising.

Article 65[1] and [2] of the Serbian Law of Contracts and Torts

(Official Gazette of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Nos. 29/78, 39/85, 45/89 – Constitutional Court Ruling, and 57/89; Official Gazette of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, No. 31/93; Official Gazette of Serbia and Montenegro, No. 1/2003 – Constitutional Charter; and Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia, No. 18/2020) stipulate that: (Official Gazette of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Nos. 29/78, 39/85, 45/89 – Constitutional Court Ruling, and 57/89; Official Gazette of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, No. 31/93; Official Gazette of Serbia and Montenegro, No. 1/2003 – Constitutional Charter; and Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia, No. 18/2020) stipulate that: [1] Should one party mislead or continue to mislead the other party with the intention of inducing him into entering into contract, the other party may request rescission of the contract even if the mistake was not of a substantial nature. [2] A party who enters into contract because of fraud shall be entitled to request damages for loss sustained. As such, in this context, an offer constitutes fraud if the form involved is misleading to such an extent that the recipient is unable to clearly comprehend the costs involved due to the offer being worded and presented so as to be objectively suitable and subjectively intended to cause the recipient to form an erroneous perception of the true features of the offer, so that its deceptive nature can be assumed even if this could have been identified by a close reading of the offer.

According to Article 208[1] of the Serbian Criminal Code (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia, Nos. 85/2005, 88/2005 – Correction, 107/2005 – Correction, 72/2009, 111/2009, 121/2012, 104/2013, 108/2014, 94/2016, and 35/2019), Whoever with intent to acquire unlawful material gain for himself or another by false presentation or concealment of facts deceives another or maintains such deception and thus induces such person to act to the prejudice of his or another’s property, shall be punished with imprisonment from six months to five years and a fine. This means that, for fraud to exist, it is not sufficient for damage to have been sustained or threatened; illicit gain is also required.

Legal recourse against foreign companies engaging in deceptive advertising practices

If a Serbian company has completed and returned the DAD form, it may argue it has been deceived into doing so, depending on the circumstances of the actual case. Companies commonly respond to these offers because they are misled into believing that they are actually confirming their TIN or other official information and that doing so will avoid their being penalised by the authorities. This, of course, is exactly what the misleading advertiser intends to happen.

A contract entered into in these circumstances can be revoked in court and the company believing itself to have been injured can seek compensation for damage, but the claim would have to be filed in the advertiser’s home country (as its jurisdiction is indicated in the fine print on the form). Doing so would inevitably cause huge costs, and there is no guarantee that the court would rule that the recipient of the offer was in fact injured, even though these cases are often very clearly examples of misleading advertising, since recipients that casually accept such offers usually fail to exercise due diligence. For instance, the court could rule that the recipient had the time and was required to read the form thoroughly before signing it, and that it had 14 days (the window indicated in the form) to revoke the contract with no consequences. The amount payable is usually designed so as to deter recipients from suing and accept the loss rather than engaging in protracted litigation. This view is supported by actual cases from a variety of countries presented above.

Moreover, the criminal liability of deceptive advertisers can only be assessed in their home countries or countries of operation. One German firm, Intercable Verlag AG, engaged in nearly identical misleading advertising practices. Its CEO was prosecuted in Switzerland, after which the company ceased to trade in Germany, but its Czech subsidiary continued to operate taking advantage of less restrictive Czech legislation.

A business that receives any suspicious form from an unofficial web site or unfamiliar company soliciting its official information and/or seeking payment should first take the time to thoroughly read the document and exercise due diligence. If it has any doubts, the recipient should ask a competent source for assistance and raise the matter with the authorities to check whether the instrument in question is in fact genuine. If the recipient has completed and returned one of these forms but is yet to pay, or has received collection notices to pressure it into payment, it should first consult a lawyer to see whether it can take legal steps to protect itself and avoid sustaining damage.