Milovan Kalezić • nov 3, 2023

Domain Names: Some Key Considerations

I Introduction

This paper aims to serve as a brief guide to domain names, their usage and relationship with trademark law, and their registration process. It seeks to present key concepts relevant for domain names and the international and national organisations maintaining and registering domain names, highlighting in particular the disputes that may arise in connection with domain name registration.

II What is in a domain name?

Domain names are, first and foremost, names assigned to host computers,[1] introduced to help average internet users navigate the global computer network. Domain names can take the form of either series of numbers or full names. Whilst numbers are important to the software used by computers to connect to the internet, people may find it easier to remember meaningful names, say <google.com> instead of <172.217.16.78>.

Domain names usually consist of two segments divided by a full stop (‘.’) (such as <vp.rs>). Exceptionally, the names can comprise three segments (<prosveta.gov.rs>), where the suffix <.rs> is a ‘domain extension’, in this case the national internet domain name for the Republic of Serbia. Domain name segments can include letters in a variety of alphabets, numbers (0 to 9), and dashes (‘-’), but may not be shorter than two or longer than 63 characters.

These names allow internet users to identify and introduce themselves to others online. The immense importance of the internet has made the choice of domain name a major business decision for all companies that wish to have a digital presence and do business online.

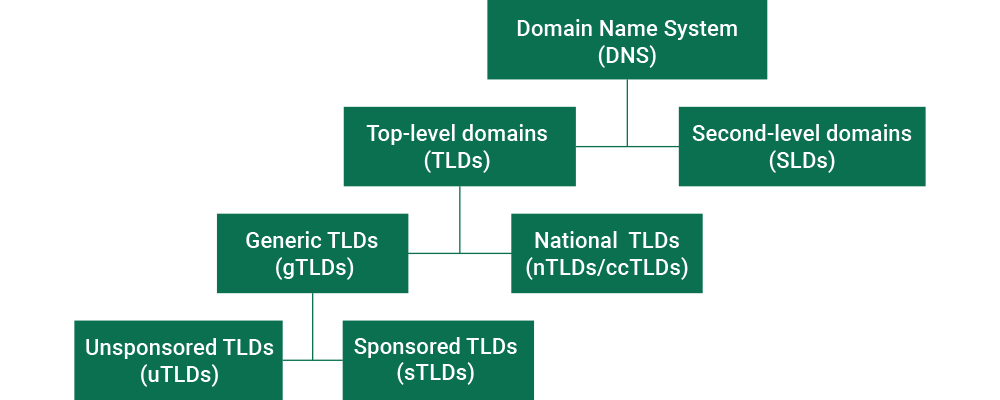

The figure below shows the hierarchy of domain names.

Generic domain names are, as a rule, reserved for one type of activity or user, such as <.aero> for the aerospace industry, <.mil> for the United States military, <.travel> for travel operators, and <.post> for postal services. The main difference between sponsored and unsponsored generic TLDs is that uTLDs are registered and managed under rules set out by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), whilst sTLDs (such as <.aero>, <.coop>, <.jobs>, and <.museum>) must comply with rules determined by their ‘sponsor’ (an organisation or group that shares common themes relevant for the domain name).

National domain names are assigned to countries and generally follow the customary abbreviations for country names, such as <.uk> for the United Kingdom, <.de> for Germany, <.it> for Italy, or <.rs> for Serbia.

Second-level domain names are the names to the left of TLD names. For instance, in <vp.rs>, <vp> is the second-level domain name. These names are particular in that anyone interested in registering an SLD must do so on the appropriate TLD extension.

Since most SLDs are registered by businesses interested in selling products or services on websites linked to those SLDs, domain names constitute marks of sorts under which the businesses advertise online. As such, SLDs often include the personal or business name of the individual or entity that has registered it. When registering an SLD, there is no requirement for the registrant to prove any rights to the mark being registered, and this can mean someone is able, inadvertently or knowingly, to register an SLD identical or substantially similar to someone else’s protected trademark and so prevent the lawful owner of that trademark to use their own mark online.

Such situations can lead to disputes between the trademark owner, who holds intellectual property rights, and the registrant, who holds rights to the registered mark which is, however, not considered an intellectual property right. What a domain name and a trademark do have in common is that both are distinctive marks that, on the one hand, make it easier for companies to do business, and, on the other, help consumers identify products and services they may be interested in.

A trademark serves to identify the source of a product or service and help consumers distinguish between the quality and value of products and services, as well as between the businesses that market them. The key function of a domain name is to allow an internet user to locate specific content online, as well as to identify a website that offers products or services they may be interested in. According to this view, the sole difference between a domain name and a trademark is that the domain name exercises its functions (in particular those of allowing distinction and localisation) in the virtual marketplace.[2]

Even though these two concepts may at first glance seem identical, where a domain name is an ‘internet trademark’, the situation is rather different. Trademarks were created as the result of government intervention in the free market to optimise social welfare, and, as such, restrict competition and create subjective intellectual property rights. Registering an SLD does not create any subjective intellectual property rights whatsoever and cannot be equated with registering a trademark.

One additional difference between a trademark and a domain name lies in the fact that a trademark is legally protected only in the state that has previously granted such protection. This means that two mutually independent and unrelated entities in different countries are able to register identical or similar trademarks with their respective national authorities. A domain name is unique globally (and this is enforced by internet registrars), so there can never be two identical names regardless of where they are registered. This means that a registrant automatically becomes able to use a domain name throughout the world, irrespective of where they have registered it.

Two people or entities are able to register identical or similar trademarks in the same country provided they are used to designate different types of products or services (with well-known trademarks being an exception to this rule). As such, two or more persons can simultaneously own identical or similar trademarks for different types of products or services, but only one of these will be able to register a domain name corresponding to that trademark.

III The role of ICANN and Serbian ccTLD manager RNIDS in registering domain names

The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), which plays a key role in registering domain names, was created in 1998 by the US Department of Commerce to co-ordinate the domain name registration system. ICANN is a non-profit group that operates in the public interest. Not being an international organisation, it is not subject to public international law.[3]

The domain name registration procedure is different for TLDs and SLDs.

Top-level domain can be generic or national. The authority for registering generic TLDs is divided between registry operators and accredited registrars. Registry operators are bodies with which ICANN has entered into an agreement assigning them the responsibility for organising, allocating, and managing TLDs, including maintaining the record of registered TLDs (the WHOIS database). Internet users do not communicate directly with the registry operator but may register domain names through registrars accredited by ICANN. Accredited registrars manage domain name reservations.

As national TLDs pertain to a particular country, territory, or geographic area, they tend to correspond to two-letter country codes as set out in the ISO 3166-1 standard.[4] Unlike generic TLDs, where registration follows ICANN rules, national TLD registration procedures are prescribed by their respective registry operators.

This means that rules for registering national TLDs are not consistent, and no attempt to ensure alignment has to date been successful. Consequently, there are currently four ccTLD registration models: (1) open; (2) some restrictions; (3) limited; and (4) no particular association with any state.

(1) In this model, ccTLDs are not restricted in terms of suitability or location, meaning that anyone, regardless of their nationality, place of residence, or location of registered office, can register a domain name with that TLD. The only limitation may be a blanket ban on registering blacklisted indecent names or the ability to subsequently revoke a TLD with such a name even if registered.[5] This is currently the dominant model worldwide.

(2) This approach envisages some restrictions to TLD registration. The registrant does not have to prove the existence of a trademark or other right in a mark or name sought to be registered as a TLD, but has to demonstrate a territorial or other connection with a country or territory whose ccTLD they are applying to use.

(3) This model limits registration in that the registrant must be territorially connected to the country in question or have the registered office of their company in that country, as well as provide proof of owning a trademark or holding rights in the name they are seeking to register as a TLD.

(4) Over the past decade, registry operators have increasingly been outsourcing their ccTLDs to foreign private companies for commercial reasons. The best known such case is the island nation of Tuvalu, which sold its top-level domain <.tv> to American company Verisign that has been marketing it to the television industry.

Second-level domains are registered as extensions to gTLDs. Unlike these generic TLDs, which are registered globally, applications to register SLDs are made with national registry operators, either dedicated legal entities or departments of other institutions designated as such by law or other regulations.

As a rule, domain names are registered by registrars authorised as such by national registry operators. The administrative procedure for registering SLDs is a first come, first served process, where the first person or entity to apply for an SLD is granted the right to use it (as the registrar does not engage in investigating domain names).

In the Serbian legal system, domain names are managed by the Serbian National Internet Domain Registry Foundation (RNIDS). This is a professional, non-partisan and non-profit organisation created on 8 July 2006 to manage Serbia’s national domain names (both <.rs> and the Cyrillic <.срб>).

Being responsible for managing the Serbian Central Registry of National Internet Domains, RNIDS performs a variety of duties related to domain names, including (1) administering the main DNS server for ccTLDs and Internationalised Domain Names (IDNs); (2) managing the publicly accessible WHOIS server for national domain names; and (3) helping to resolve disputes in assigning domain names.

IV Domain name disputes

A registrar may inadvertently or knowingly register someone else’s trademark as a domain name. Domain name registration disputes can be divided into two broad categories: (1) disputes between parties acting in good faith; and (2) disputes involving abusive registrants.

(1) Disputes between parties acting in good faith can further be sub-divided into an additional two categories, namely: (a) disputes where both parties own trademarks they wish to register as a domain name (where both hold the same type of intellectual property rights, where their intellectual property rights differ, and where one party holds intellectual property rights and the other party a different right in the same mark); and (b) disputes where one party holds a right in a mark it wishes to register as a domain name and the other party holds no such right but uses it as a domain name in good faith.

(2) Disputes involving abusive registrants are much more common and occur where an abusive party registers a domain name that is identical or substantially similar to a trademark owned by another party. There are several types of such domain name abuses:

1) Abuses that constitute trademark infringement (For there to be trademark infringement, the registrant must be marketing their products or services on the website linked to the disputed domain name. In these cases the trademark infringement is created by the activities undertaken on the website rather than by the sole act of registering the domain name.) –

a. Cyber piracy is the use of another’s trademark to drive traffic to a website and so generate advertising revenue or online sales. Notably, as a rule these websites redirect traffic from an abusively registered domain name to a different website hosting an online store, so misleading internet users as to the origin of the goods or services marketed on that website.

b. Typosquatting means registering a domain name similar to another’s trademark but deliberately containing typos commonly made by internet users when inputting internet addresses. The intent here is to profit from redirecting internet traffic from a website using the abusively registered domain name to a different website hosting an online store, so misleading internet users as to the origin of the goods or services marketed on that website.

2) Abuses infringing exclusively on the legitimate interests of the trademark owner (For there to be infringement of legitimate interests, the registrant must have registered an internet domain not to market their own products or services but to prevent the trademark owner from using their trademark online or make the domain name inaccessible to the trademark owner.) –

a. Cybersquatting or domain name hijacking is the practice of registering a domain name identical to another’s trademark with the intention of subsequently selling the domain name to the trademark owner. The rationale is that the trademark owner will value the domain name so greatly that it will be prepared to purchase it at a disproportionately high price.

b. Pseudo-cybersquatting means registering a domain name identical to another’s trademark without the intention of either using it or subsequently selling it to the trademark owner. This prevents the trademark owner from registering the domain name and using it for their online presence.

(3) Other abuses that do not clearly belong to either of the two categories above –

a. Cybersmearing is the registration of a domain name consisting of a trademark and a phrase that has a negative connotation. This practice constitutes a conflict between freedom of speech and trademark protection. It could mean either trademark infringement (it could be argued, for instance, that internet users may not understand that the added word or phrase has a negative connotation, and so may be misled as to whether the website and the trademark owner are associated) or infringement of the trademark owner’s legitimate interests (where the owner’s right to use their trademark online may be restricted, with the argument that freedom of speech can be exercised elsewhere on the internet and not on a website that uses a disputed domain name).

b. Reverse cybersquatting or reverse domain name hijacking is a practice where a trademark owner attempts to hijack a domain name by abusively litigating against a registrant for alleged cybersquatting. This topic will be explored in greater detail below.

c. Registering an expired (‘dropped’) domain name. Domain name registrations expire if not regularly renewed, which requires paying a fee to the registrar. A third party can exploit the failure of an owner to renew this registration to take control of a domain name and can then offer to sell the name back to the original registrant at an inflated price.

Trademark owners have recourse to three options to counter domain name abuse: (1) seek to buy the domain name from the cybersquatter (which may not be cost-effective as the prices are generally disproportionately high and doing so only incentivises repeated abuse); (2) litigate for trademark infringement; and (3) litigate and seek to resolve the dispute using the Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (UDRP).

Litigation

Trademark owners tend to seek legal redress against parties that register domain names identical or substantially similar to their trademarked names.

Where a domain name has been registered and is in use, registrant data are generally available on the website that uses the domain name. Otherwise, the data can be found in the WHOIS database maintained by the relevant registry operator. For there to be trademark infringement, the registrant must be marketing their products or services on the website that uses the disputed domain name. In these cases the trademark infringement is created by the activities undertaken on the website rather than by the sole act of registering the domain name. If there is no website linked to the domain name, or if there is one but it is not used for advertising, the courts tend to find no trademark infringement as the trademark is not used to misrepresent products or services.

There is no specific Serbian law that can be relied on in domain name disputes, with local courts applying the Trademark Law and the Civil Procedure Law. Establishing cross-border jurisdiction is a notable issue in domain name cases, where both parties will often be foreign nationals. Case law suggests that cross-border and territorial jurisdiction is conferred on courts of the place where the damage occurred, as otherwise, paradoxically, plaintiffs could seek legal redress in a state where their rights are not recognised at all. Another feature of domain name cases is that the claim to revoke or transfer the registration of a domain name is an accessory claim, whilst the primary claim will petition the court to find infringement of a subjective intellectual property right.

UDRP procedure

In a bid to create an alternative domain name dispute resolution mechanism, on 24 October 1999, at the motion of the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO), ICANN adopted:

1. the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP), and

2. Rules for Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP Rules).

The UDRP procedure set a new international standard for resolving domain name disputes that aimed not only to provide an enforcement mechanism that would help safeguard intellectual property rights, but also to prevent disputes by incentivising owners of trademarks and other intellectual property rights to register domain names.

Worldwide, ICANN has accredited the WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center Geneva, National Arbitration Forum, Arab Center for Domain Name Dispute Resolution, Czech Arbitration Court, and Asian Domain Name Dispute Resolution Centre to resolve domain name disputes using UDRP rules.

Apart from UDRP rules, these accredited centres can introduce additional regulations, for their own use and within their own remits, that govern their fees, instructions, communication with relevant accredited centres or arbitration panels, and the like. For instance, the WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center Geneva was the first such entity to enact WIPO Supplemental Rules for the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy. These supplemental regulations may not contravene general UDRP rules, which always prevail in the event of a conflict.

UDRP procedure in Serbia

In Serbia, disputes over registered <.rs> and <.срб> domain names are heard by the Committee for the Resolution of Disputes Relating to the Registration of National Internet Domains at the Serbian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (SCC). The Committee is modelled after institutional arbitration tribunals that have a long history at the SCC, and its structure comprises a Presidency and Tribunals, with the Secretariat of the Permanent Court of Arbitration Attached to the SCC providing support. The Presidency is composed of: (1) President; (2) Vice-President; and (3) Committee Secretary. The President and Vice-President of the Committee are appointed and dismissed by the Managing Board of the SCC from the ranks of listed arbiters to four-year terms of office, and may be re-appointed. The Committee Secretary is be appointed by the President of the Serbian Chamber of Commerce from the ranks of SCC staff.

The Committee applies the Rules of Procedure for the resolution of disputes relating to the registration of national internet domain names (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia Nos. 31/11, 24/12, 67/14, and 61/16), adopted by the RNIDS Conference of Co-Founders on 18 December 2010. The rules contain both substantive and procedural provisions, with the substantive content patterned after UDRP.

Domain name disputes are heard by a three-member Tribunal. One member is nominated by the complainant, who provides a list with the names of three arbiters from the List of Arbiters when submitting their petition. The Committee Secretary then assigns the complainant the first available arbiter from the list supplied. The second member of the Tribunal is nominated by the registrant, who is also required to provide a list with the names of three arbiters from the List of Arbiters in the registrant’s response to the complaint. The Committee Secretary will assign the first available arbiter to the registrant. Where the complainant and/or the registrant do not nominate arbiters, or where, for any reason, the nominated arbiters are unable to take part in the arbitration proceedings, the Committee Presidency appoints an arbiter for each party to the dispute from the List of Arbiters. The designated arbiters select a third arbiter from the List of Arbiters as Tribunal Chair within seven days, and if they fail to do so within this period the chair is selected by the Committee Presidency.

Open cases are promptly communicated by the Committee Secretariat to RNIDS, which then flags the disputed national domain names to prevent their transfer or changes to their registration data until the dispute resolution procedure is complete. The Secretariat also forwards the complaint and any accompanying documents electronically to the registrant, who may then respond within 15 days of receiving the complaint. Oral hearings are held only where the Tribunal deems them appropriate and where conditions to do so are met. The Committee Secretariat notifies the parties of the date and place chosen for any such hearing. Where the Tribunal deems that the written filings and evidence are sufficient for a decision to be made, it may propose to the parties that the decision in the case be made without an oral hearing, and the parties have five days to agree or object.

The parties may also mutually agree to petition the arbitration Tribunal to render a decision without an oral hearing. If one of the parties objects to this, the Tribunal will decide whether to convene an oral hearing. As a rule, oral hearings take place on the Committee’s premises, but the Tribunal may choose to hold it elsewhere subject to a duly reasoned petition of either party. Oral hearings are not open to the public unless the parties agree otherwise. Domain name dispute cases are steered by the Tribunal Chair, who questions parties, calls evidence, and allows the parties and their legal representatives and proxies to take the floor. A domain name dispute resolution case can end in either (1) a final decision or (2) a conclusion to discontinue the proceedings.

Arbitration decisions are served electronically on the parties and delivered to the RNIDS and published on its website. These decisions are final and may not be appealed. The decisions are enforced within ten days of being received by RNIDS, except where a party has submitted proof of having brought a civil case before the competent court, in which case enforcement is postponed until the court ruling in that case becomes final.

The Rules of Procedure for the resolution of disputes relating to the registration of national internet domain names provide a set of criteria for the Tribunal to apply when deciding whether to order the revocation or transfer of a domain name. These are:

(1) The national domain name is identical to the complainant’s trademark or is similar to it to the extent that it might create confusion and mislead the market;

(2) The registrant has no right to use or legitimate interest in using the disputed domain name;

(3) The registrant has registered and used the domain name in bad faith and contrary to good business practice.

The registrant will be deemed to have a legitimate interest in using a domain name if:

(1) they had been using the domain name for commercial purposes, in accordance with good business practice and in good faith, prior to any knowledge of a complaint having been brought; or

(2) prior to a complaint having been brought, they were already publicly known as the owner of that domain name, regardless of the fact that they had not registered the disputed trademark; or

(3) they are using the domain name purely for non-commercial purposes, even where the domain name is identical or substantially similar to the complainant’s trademark, with no intention of misleading consumers or other market participants as to the origin of any products or services marketed.

A domain name will be deemed to have been registered or used contrary to good business practice and in bad faith if it is proven that:

(1) the registrant registered a domain name primarily with the aim of selling or leasing it to the complainant who is the owner of a trademark identical or substantially similar to the registered domain name, or of selling or leasing the domain name to a competitor of the complainant, as evidenced by a disproportion between the registration fee for the domain name and the price at which it has been offered for sale;

(2) the registrant registered a domain name to prevent the trademark owner from registering their trademark as a domain name;

(3) the registrant registered a domain name to cause damage to a competitor;

(4) the registrant used a domain name that is identical or substantially similar to the complainant’s trademark primarily to attract internet traffic to the registrant’s website or other online service for commercial purposes, in doing so creating confusion as to the origin of products marketed or services provided on such website or via such online service.

Domain name registration in advance of trademark registration

Where registration of a domain name has preceded that of a trademark, arbitration panels have tended to find no trademark infringement that would result in the revocation or transfer of a domain name registration. In most of these cases the reason was the perceived absence of the third substantive requirement, namely the lack of bad faith on the part of the registrant. The arbitrators usually ruled that the registrant was not and could not have been aware of the existence of any trademark as the domain name had been registered before the complainant had formally protected their intellectual property. That being said, a registrant may be found to have acted in bad faith if it had anticipated that a trademark would be registered.

One example is provided by the 2016 case of Insight Energy Ventures LLC v. Alois Muehlberger, L. M.Berger Co. Ltd[6] over the domain name powerly.com. Insight Energy Ventures LLC, the complainant, owned several US trademarks containing the names POWERLY and POWERLEY, which it applied for in 2015 and formally registered in 2016. The respondent, Alois Muehlberger of L. M. Berger Co. Ltd., registered the disputed domain name on 19 March 2004 but never set up a website associated with it. The complainant alleged that the respondent owned more than 120 domain names, none of which appeared to be in use, which he held to resell for a profit. As the complainant had rights in the trademarks POWERLY and POWERLEY, any sale of the disputed domain name to a third party would result in confusion. The administrative panel found that the respondent had registered the disputed domain name ten years before the complainant had registered any of their trademarks, as well as that the complainant had provided no evidence to show that the respondent was, or should have been, aware of the complainant or its trademarks at the time the complaint was filed, and certainly not at the time the respondent registered the disputed domain name. Further, the panel ruled, the complainant had provided no evidence to suggest that the complainant was even operating in 2004, at the time the disputed domain name was registered: according to the complainant’s website, this brand was created in approximately late 2014. Given this, there was absolutely no basis on which the panel was willing to find that the disputed domain name was registered or used in bad faith. There were no grounds or evidence to suggest the respondent was acting in bad faith.

Domain name registration in anticipation of trademark registration

In most cases, a domain name registered before a trademark will not result in the finding of bad faith on the part of the registrant. However, at times a registrant may anticipate that a trademark will be registered and purchase a domain name ahead of the future trademark owner, so preventing the intellectual property holder from using their trademark online. This can occur if the domain name is registered (1) immediately before or after a corporate merger; (2) using insider information (such as by a former employee); (3) after a product or service receives significant media attention (for instance, ahead of an announced launch); and (4) after an application to register a trademark has been made.

One such example is the 2017 case of INTERTEX, Inc. v. Shant Moughalian[7] in connection with three domain names, <bluedri.com>, <grizzlytarps.com>, and <soleaire.com>. The complainant, INTERTEX, Inc. of Azusa, California, United States of America owned three US trademarks, namely GRIZZLY TARPS, registered on 15 May 2012, BLUEDRI, registered on 16 August 2016, and SOLEAIRE, registered on 23 August 2016. The respondent, Shant Moughalian, Contess, Inc. of San Dimas, California, registered three domain names: <grizzlytarps.com>, on 10 August 2010, <bluedri.com>, on 18 July 2012, and, lastly, <soleaire.com>, on 25 July 2012. The complainant contended that the respondent had no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the domain names because he was not given authority to use them or the complainant’s trademarks. The complainant explained that the complainant had hired the respondent to conduct marketing for the company in 2004 and employed him through 2015. During his employment, the respondent was instructed to register various domain names on behalf of the complainant, including the domain names in this case. The respondent’s employment was terminated in 2015, and, unbeknownst to the complainant, the respondent then either initially named himself as registrant of the domain names or transferred ownership of them to himself at a later time, without the complainant’s authorisation. The domain names were not being used for any legitimate purpose, alleged the complainant, but rather to prevent the complainant from reflecting its trademarks with the corresponding domain names and to divert traffic seeking the complainant’s products to non-operational websites. The administrative panel found that the respondent and his company were competitors to the complainant and that the respondent had not been commonly known by the domain names nor was using them for legitimate purposes but instead used to hinder the complainant’s operations. The panel did find the domain names were registered prior to the trademarks, which could be construed as the registration not having been in bad faith because the registrant could not have contemplated the complainant’s then non-existent right. However, in the instant case, where the parties had had a pre-existing relationship, the respondent was found to be in a position to contemplate the complainant’s plans for future product brand names and related trademarks and so obstruct the complainant’s business.

Reverse domain name hijacking

Reverse domain name hijacking, or reverse cybersquatting, is defined by UDRP rules as ‘using the Policy in bad faith to attempt to deprive a registered domain-name holder of a domain name’. Under UDRP Paragraph 15(e), if the Panel ‘finds that the complaint was brought in bad faith, for example in an attempt at Reverse Domain Name Hijacking or was brought primarily to harass the domain-name holder, the Panel shall declare in its decision that the complaint was brought in bad faith and constitutes an abuse of [the UDRP rules]’. Arbitration panels have tended to rule that the failure of a complaint is not in and of itself reason enough to find an attempt at reverse domain name hijacking, which has resulted in developed the following set of circumstances to be taken into consideration when making decisions in these matters:

(1) facts suggesting the complainant was aware he could not meet any of the three required substantive criteria (absence of complainant’s trademark or clear awareness of the right or legitimate interest of the registrant or clear awareness of the registrant’s acting in good faith);

(2) facts suggesting the complainant was aware he could not succeed in his complaint given the facts available to him before he lodged the complaint, either from the website linked to the disputed domain name or from readily accessible public sources such as the WHOIS database;

(3) giving fictitious evidence or otherwise attempting to mislead the arbitration panel;

(4) knowingly giving incomplete material evidence;

(5) failure by the complainant to notify the arbitration panel in the event of a repeated dispute;

(6) lodging a complaint after unsuccessfully attempting to obtain the disputed domain name from the registrant without valid legal grounds;

(7) lodging a complaint based only on allegations with no substantiating evidence.

Case law of the Serbian Committee for the Resolution of Disputes Relating to the Registration of National Internet Domains

This final section provides a selection of notable Committee decisions available on the RNIDS website.

Decision regarding the domain name <playstation.rs> of 21 November 2021, Case No. TD-2/21, Sony Interactive Entertainment Inc., Tokyo, Japan v. Dragan Mrdaković.

Decision regarding the domain name <ehrle.co.rs> of 18 June 2019, Case No. TD-1/19, Ehrle GmbH Germany v. Ehrle Sistemi doo za trgovinu i usluge Veternik, with the dissenting opinion of Arbiter Vladimir Marenović.

Decision regarding the domain name <adamall.rs> of 12 October 2018, Commercial Developments doo Beograd, where the Committee dismissed the complaint.

[1] A host computer is a computer that provides information, services, or other resources to other computers connected to the internet.

[2] D. Popović, Imena internet domena i pravo intelektualne svojine, Institut za uporedno pravo, Monografija, Beograd 2005, p 51.

[3] D. Popović, Registracija naziva internet domena i pravo žiga, Pravni fakultet Univerziteta u Beogradu, Monografija, Beograd 2014.

[4] In 1974, the International Standards Organisation (ISO) adopted its ISO 3166 standard, which sets out three different codes for each state and territory (ISO 3166-1, ISO 3166-2, and ISO 3166-3). ISO 3166-1 is a list of codes for country names and dependencies, ISO 3166-2 is the list of codes for administrative divisions of countries, and ISO 3166-3 is the list of codes for formerly used for countries and subdivisions.

[5] Torsen Bettinger, Allegra Waddell, Domain name law and practice – An international handbook, Oxford University, press 2005.

[6] WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center: Case No. 2016-2010, Insight Energy Ventures LLC v. Alois Muehlberger, L.M.Berger Co.Ltd

[7] WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center: Case No. 2017-0480, INTERTEX, Inc. v. Shant Moughalian